By Karl Anderson

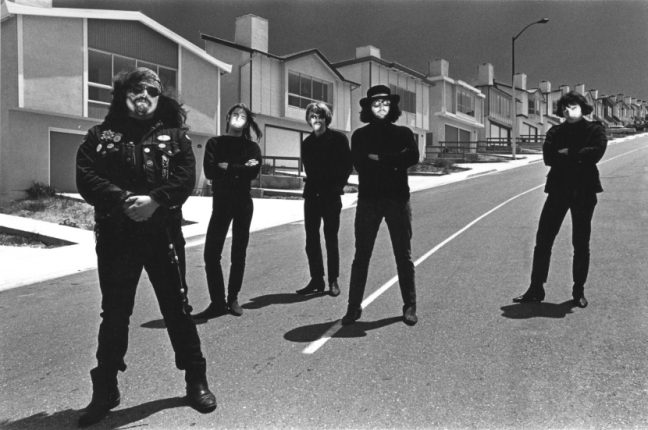

The end of era the Passing of legendary photographer Bob Seidemann. Bob took some of the most iconic photos of the 1960s. A true visionary that was able to capture the mood of the 60’s in eye of a lens.

While still living in New York, Seidemann learned how to take pictures from a dance-photographer named Tom Caravaglia, and his career behind a lens blossomed in San Francisco, where he was drawn to the city’s psychedelic music scene. In particular, he got tight with the members of Big Brother and the Holding Company, with whom he lived for a while in nearby Marin County, and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, for whom he designed the cover of the incomparable guitarist’s first solo album. By the late 1960s, Seidemann was famous—in some circles, infamous—as a rock photographer.

“To be honest with you, I wasn’t very interested in the music,” he admits today. “It was the scene, you know? I didn’t intend to become a documentarian; I was just hanging out, a friend of these people. I had a little bit of skill with the camera, able to do stuff that did not require a lot of expertise. As their work progressed, so did mine.”

His progression as a photographer included surreal “head-shop” posters of the Grateful Dead , two portraits, including a nude, of Janis Joplin , and a collaboration with acclaimed rock-poster artist Rick Griffin (“He died about 500 years too soon.”).

And then, in 1969, Seidemann shot a photograph he titled “Blind Faith,” which Eric Clapton used as the name of his post-Cream super-group, as well as for the cover of the band’s only album. Notoriously, it featured a nude 11-year-old girl named Mariora Goschen (whose parents had given permission for the shoot) holding an airplane-like spaceship made by a London jeweler named Mick Milligan.

Record retailers in the United States promptly freaked out. It was not just Goschen’s nakedness; they were convinced that the object in her hand was blatantly and deliberately phallic, spurring a new cover featuring a more traditional portrait of the band for the album’s U.S. release. But Seidemann never intended the imagery to be titillating: “To symbolize the achievement of human creativity and its expression through technology,” he later wrote, “a spaceship was the material object. To carry this new spore into the universe, innocence would be the ideal bearer, a young girl, a girl as young as Shakespeare’s Juliet. The spaceship would be the fruit of the tree of knowledge and the girl, the fruit of the tree of life.”

“Blind Faith,” Seidemann told me recently, was chosen as the title of the photograph because “that’s what she represented.” At last check, the original album cover was a collector’s item, and a Seidemann print of the image is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

For the next decade or so, Seidemann leveraged his connections in the music industry to become one of the most respected rock photographers of his generation. In addition to his work for Jerry Garcia and Blind Faith, he created covers for Jackson Browne and Neil Young. But Seidemann was never comfortable in the music racket, which author Hunter S. Thompson once described as “a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs.” There’s little doubt Seidemann shared these sentiments.

“I was working in the music business,” Seidemann says today, “and I often thought, ‘what a low-life crowd this music industry is.’ I wanted to find something to do that I could be really proud of.”

“I love those two lines converging here,” he says, pointing to the dead-level horizon line I have failed to notice but is now obviously visible at the left edge of the picture, These are the sorts of lines, Seidemann suggests, that Tom Caravaglia taught him to look for all those years ago in New York, before he ever imagined he would one day earn his keep taking pictures of people like Janis Joplin or Jimmy Doolittle.

I mumble something about how dumb it must seem to him that I had not noticed the horizon line until he had pointed it out. But Seidemann just looks at me through those white eyeglass frames of his, a twinkle in his eyes. “That’s the arty part, the stuff they pay me the big money for,” he says with a gentle smile. That’s the stuff, one might add, a photographer could feel proud of.

Bob was a true visionary and wonderful human being. He will be missed but the genius of his photography will live on for many years to come. His photography is truly some of the best of the 1960s.

I aam so glad he was recognized before he passed. And he was a good person too.

LikeLike

Thank you Kathy for your kind words

He was a good person too

Belinda Seidemann

LikeLike

Hello Belinda, Thank you for posting. Yes he was a good person and a great photographer. Blessing to you

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Music of Our Heart and commented:

A visionary photographer joins the great beyond. I did not realize he shot the Blind Faith album cover. I have to locate my copy and see what condition it’s in.

LikeLike